History

Pluto has a unique and storied history among the nine major celestial bodies in the Solar System. Here are some of its more interesting features:

Discovery

In the , Urbain Le Verrier used Newtonian mechanics to predict the position of the then-undiscovered planet Neptune after analysing perturbations in the orbit of Uranus. Subsequent observations of Neptune in the late 19th century led astronomers to speculate that Uranus's orbit was being disturbed by another planet besides Neptune.

In , Percival Lowell – a wealthy Bostonian who had founded the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, in – started an extensive project in search of a possible ninth planet, which he termed "Planet X". By , Lowell and William H. Pickering had suggested several possible celestial coordinates for such a planet. Lowell and his observatory conducted his search until his death in , but to no avail. Unknown to Lowell, his surveys had captured two faint images of Pluto on and , but they were not recognized for what they were. There are fourteen other known prediscovery observations, with the oldest made by the Yerkes Observatory on .

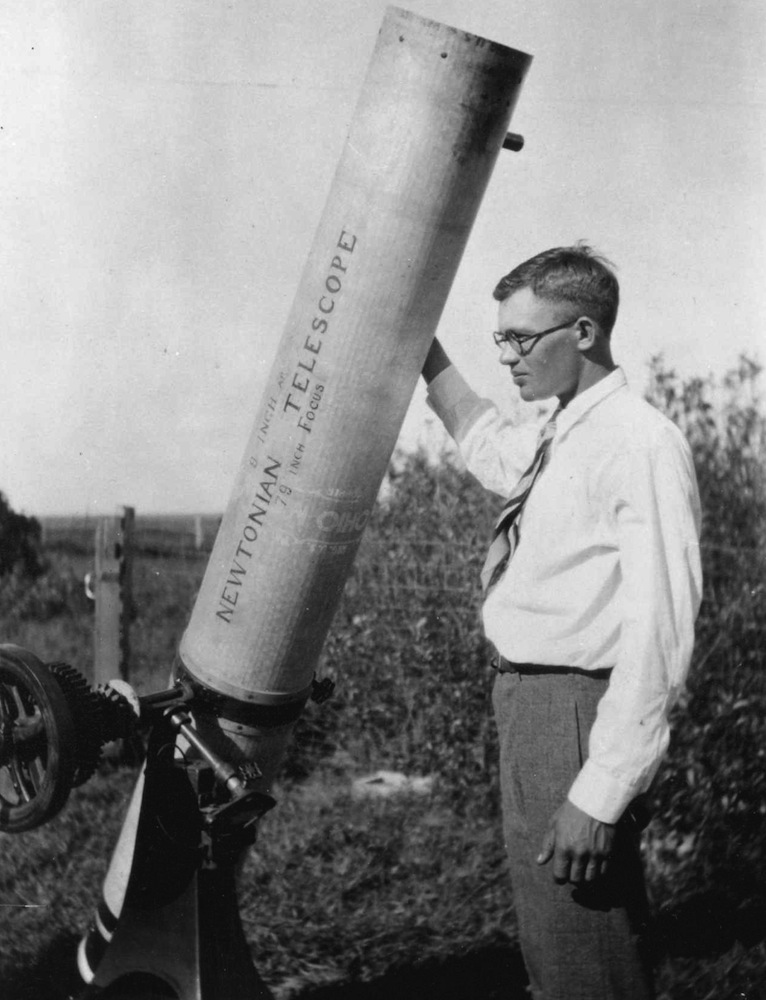

Percival's widow, Constance Lowell, entered into a ten-year legal battle with the Lowell Observatory over her late husband's legacy, and the search for Planet X did not resume until . Vesto Melvin Slipher, the observatory director, summarily handed the job of locating Planet X to 23-year-old Clyde Tombaugh, who had just arrived at the Lowell Observatory after Slipher had been impressed by a sample of his astronomical drawings.

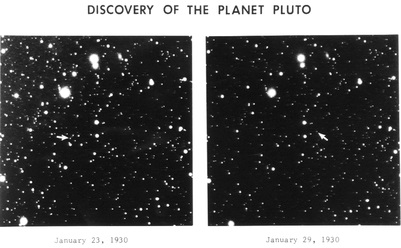

Tombaugh's task was to systematically image the night sky in pairs of photographs, then examine each pair and determine whether any objects had shifted position. Using a blink comparator, he rapidly shifted back and forth between views of each of the plates to create the illusion of movement of any objects that had changed position or appearance between photographs. On February 18, 1930, after nearly a year of searching, Tombaugh discovered a possible moving object on photographic plates taken on January 23 and 29 of that year. A lesser-quality photograph taken on January 21 helped confirm the movement. After the observatory obtained further confirmatory photographs, news of the discovery was telegraphed to the Harvard College Observatory on .

Name

The discovery made headlines around the globe. The Lowell Observatory, which had the right to name the new object, received more than 1,000 suggestions from all over the world, ranging from Atlas to Zymal. Tombaugh urged Slipher to suggest a name for the new object quickly before someone else did. Constance Lowell proposed Zeus, then Percival and finally Constance. These suggestions were disregarded.

The name Pluto, after the god of the underworld, was proposed by Venetia Burney (–), a then eleven-year-old schoolgirl in Oxford, England, who was interested in classical mythology. She suggested it in a conversation with her grandfather Falconer Madan, a former librarian at the University of Oxford's Bodleian Library, who passed the name to astronomy professor Herbert Hall Turner, who cabled it to colleagues in the United States.

The object was officially named on . Each member of the Lowell Observatory was allowed to vote on a short-list of three: Minerva (which was already the name for an asteroid), Cronus (which had lost reputation through being proposed by the unpopular astronomer Thomas Jefferson Jackson See), and Pluto. Pluto received every vote. The name was announced on . Upon the announcement, Madan gave Venetia £5 (equivalent to 300 GBP, or 450 USD in 2014) as a reward.

The final choice of name was helped in part by the fact that the first two letters of Pluto are the initials of Percival Lowell. Pluto's astronomical symbol (♇, Unicode U+2647, ♇) was then created as a monogram constructed from the letters “PL”. Pluto's astrological symbol resembles that of Neptune (♆) but has a circle in place of the middle prong of the trident (🔱).

Planet X Disproved

Once Pluto was found, its faintness and lack of a resolvable disc cast doubt on the idea that it was Lowell's Planet X. Estimates of Pluto's mass were revised downward throughout the 20th century.

Astronomers initially calculated its mass based on its presumed effect on Neptune and Uranus. In , Pluto was calculated to be roughly the mass of Earth, with further calculations in bringing the mass down to roughly that of Mars. In , Dale Cruikshank, Carl Pilcher and David Morrison of the University of Hawaii calculated Pluto's albedo for the first time, finding that it matched that for methane ice; this meant Pluto had to be exceptionally luminous for its size and therefore could not be more than 1 percent the mass of Earth. (Pluto's albedo is 1.4–1.9 times that of Earth.)

In 1978, the discovery of Pluto's moon Charon allowed the measurement of Pluto's mass for the first time: roughly 0.2% that of Earth, and far too small to account for the discrepancies in the orbit of Uranus. Subsequent searches for an alternative Planet X, notably by Robert Sutton Harrington, failed. In , Myles Standish used data from Voyager 2's flyby of Neptune in , which had revised the estimates of Neptune's mass downward by 0.5%—an amount comparable to the mass of Mars—to recalculate its gravitational effect on Uranus. With the new figures added in, the discrepancies, and with them the need for a Planet X, vanished. Today, the majority of scientists agree that Planet X, as Lowell defined it, does not exist. Lowell had made a prediction of Planet X's orbit and position in 1915 that was fairly close to Pluto's actual orbit and its position at that time; Ernest W. Brown concluded soon after Pluto's discovery that this was a coincidence, a view still held today.

Classification

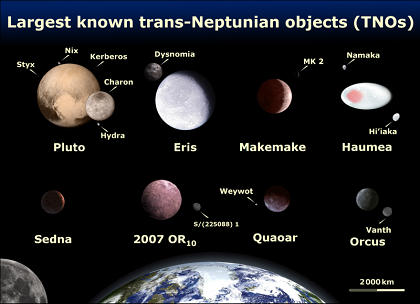

From onward, many bodies were discovered orbiting in the same area as Pluto, showing that Pluto is part of a population of objects called the Kuiper belt. This made its official status as a planet controversial, with many questioning whether Pluto should be considered together with or separately from its surrounding population. Museum and planetarium directors occasionally created controversy by omitting Pluto from planetary models of the Solar System. The Hayden Planetarium reopened—in , after renovation—with a model of only eight planets, which made headlines almost a year later.

As objects increasingly closer in size to Pluto were discovered in the region, it was argued that Pluto should be reclassified as one of the Kuiper belt objects, just as Ceres, Pallas, Juno and Vesta eventually lost their planet status after the discovery of many other asteroids. On , astronomers at Caltech announced the discovery of a new trans-Neptunian object, Eris, which was substantially more massive than Pluto and the most massive object discovered in the Solar System since Triton in . Its discoverers and the press initially called it the tenth planet, although there was no official consensus at the time on whether to call it a planet. Others in the astronomical community considered the discovery the strongest argument for reclassifying Pluto as a minor planet.

IAU Classification

The debate came to a head on , with an IAU resolution that created an official definition for the term "planet". According to this resolution, there are three conditions for an object in the Solar System to be considered a planet:

- The object must be in orbit around the Sun.

- The object must be massive enough to be rounded by its own gravity. More specifically, its own gravity should pull it into a shape defined by hydrostatic equilibrium.

- It must have cleared the neighborhood around its orbit.

Pluto fails to meet the third condition, because its mass is only 0.07 times that of the mass of the other objects in its orbit (Earth's mass, by contrast, is 1.7 million times the remaining mass in its own orbit). The IAU further decided that bodies that, like Pluto, meet criteria 1 and 2 but do not meet criterion 3 would be called dwarf planets. On , the IAU included Pluto, and Eris and its moon Dysnomia, in their Minor Planet Catalogue, giving them the official minor planet designations "(134340) Pluto", "(136199) Eris", and "(136199) Eris I Dysnomia". Had Pluto been included upon its discovery in , it would have likely been designated 1164, following 1163 Saga, which was discovered a month earlier.